NOTE: Ernie Hange passed away on Aug. 20, 2022 — only four months after sitting for this interview. He was 91. In his obituary, he was described as “a hardworking, humorous, witty man who could brighten the room with his presence.” We hope this life story reflects those qualities.

When a visitor asks permission to remove her pandemic mask, Ernie Hange and his wife, Marie, say yes. “Halloween is over,” he quips.

With that, and the twinkle in his eye, the guest knows that an afternoon with this couple will be a fun trip through time. Over the course of several hours, they share memories of childhood in an area so different from how it is today, it’s hard to create a mental picture.

Ernie Hange — pronounced like “change” without the “c” — entered the world in April 1931. His parents, William Hange and Anna Marie Kuhn, had been married at the Washington Chapel in Valley Forge National Park. The venue was unusual for a family steeped in the Mennonite faith. But it was the middle ground for his mother, who was raised as a Roman Catholic. Her interfaith marriage was difficult for her family, Ernie remembers. But Anna came to appreciate the Mennonite faith, and the family worshipped at Line Lexington Mennonite Church.

Ernie’s father grew up with two older brothers, his father Joseph and mother Lizzie — all of whom lived in the home of his grandfather, Levi Hange. The multi-generational family lived in Fairhill, Bucks County, where Levi owned his farm and Joseph worked.

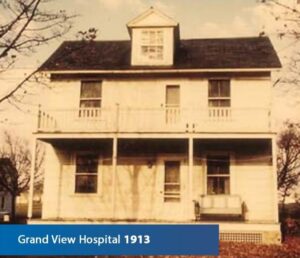

By the time Ernie came on the scene, his Hange family had been living in Montgomery and Bucks counties since at least the early 1800s. He was born in the old stone building that used to be part of Grand View Hospital, which itself was only 18 years old in 1931. Ernie weighed 3 lbs., 15 ounces and spent the first five weeks of his life in the hospital, being fed goat’s milk with an eye dropper and carried in a shoe box. But he did come home and spent his childhood in Hilltown Township.

Grand View Hospital in 1913. Image from Facebook.

In 1938, Willie Hange bought 4 acres from the Spengel sisters along the two-lane Souderton Pike on the outskirts of Souderton Borough. This is where Ernie did his chores to help on the truck farm, where his father grew produce of all sorts and raised chickens, pigs and other farm animals.

Willie was a “huckster” — a street peddler, especially of fruits and vegetables. Willie would take his farm products and sell them in Philadelphia and other areas, making a living to help support his family during the Great Depression.

Their neighbors in the 1940 Census included Frankenfields, Grobs, Flucks, Moyers, Alderfers and Gehmans. Nine-year-old Ernie had completed 2nd grade. The income from the truck farm was in addition to Willie’s job as a presser in a coat factory. Anna also worked as a pocket maker at the coat factory, and their combined income was $2,000.

Later in life, Willie was a self-employed carpenter — a profession several of his ancestors also practiced. Anna, according to her obituary, worked at the Leading Upholstery Co. before becoming a seamstress for the SunLite Shop, both in Souderton.

Ernie began his school years at the one-room Pennville school on Old Bethlehem Pike and School House Road in Hilltown. The distance to walk from his home on “Road 113” was just less than 1 mile each way — in rain, snow or sun. He recalls that the neighbors’ children would join in the trek so that they arrived at school as a group.

Grace Allebach was the teacher for grades 1 through 4. There was a bell in the belfry that would be rung to call the children in for class or when they went out for recess. Anyone close by could follow the day’s schedule by the ringing of the bell. The students carried their lunch in a paper bag, perhaps peanut butter and jelly with a piece of fruit. A candy bar was a special treat rarely enjoyed. From grades 5-8, Ernie attended the Gehman school in Perkasie — arriving there on a blue school bus.

After the United States entered World War II, Ernie remembers how the atmosphere in the area changed. Wardens would walk up and down Road 113 ensuring that no home had a light showing. He also recalls that rationing came into effect, limiting access to products such as sugar and gasoline. Not because of shortages, he says, but because much of the supply was reserved for use in the war effort. But living on a farm meant that his family was largely self-sufficient with respect to food.

After 8th grade, at about 14, his formal education was complete, and Ernie began his lifelong career as a carpenter. This was not unusual; there was no high school, so most children began working after 8th grade. All children had the same middle name, Ernie says: w-o-r-k.

In 1947, he was making 40 cents an hour doing carpentry work for a local minister, who had a business in addition to his congregation. After two years, a help-wanted ad in the Souderton Independent took him — riding his Cushman motor scooter for which he bought gas at 18 cents a gallon — to the office of Howard Landis, who was looking for a carpenter and paying 45 cents an hour. Ernie went back to his employer to see if he would match those 45 cents. When he didn’t, Ernie went to work for Landis. After six weeks, he received his first paycheck, made out by Mrs. Landis, in a brown envelope and was surprised to find a lot more money than expected. When he asked Howard Landis about the amount, Ernie was told he had proven himself and was rewarded with an hourly 65 cents. What a windfall!

Now he was ready to get on with his adult life. In 1950, he decided it was time to start dating and asked his friend Paul Meyers if he knew of anyone. Yes, there was a girl, and on a Monday evening, Ernie put on his white shirt and tie and went to her home. A knock on the door brought a young lady. But this was not Marie Leatherman, and she went off to get her sister. Marie and Ernie spoke through the screen door, Ernie asking if she would like to go out on the following Saturday and she replying, yes that would be nice. In those days there wasn’t much in the way of entertainment or restaurants. But they continued visiting and in 1952, a wedding was planned. Marie shows their wedding photo and the simple, classic white dress she paid $5 to have made.

No rings were exchanged; their faith frowned on flashy jewelry. Instead, Ernie gave Marie a cedar chest from Renner Brothers in Perkasie as an engagement gift. It’s still with them in their bedroom. And Marie gave him a desk, again still with them in their living room.

After the wedding, they went off in his 1948 Pontiac to Florida for two weeks. She had a dress made from a bag containing animal feed sold by Moyer & Son in Souderton. The cotton fabric of the bag was often reused by the women for aprons and clothing.

The couple moved into their first apartment in Perkasie, for which they paid $35 a month. Money was tight, but neighbors helped neighbors. They would shop for groceries, and if the cash was not enough to pay the bill, the difference went on account, and it would be paid at the next visit. Sometimes Ernie would do work for the owner, and that would pay down the balance.

If a bigger expense came up — as when Ernie needed to buy two new tires for his truck — you could visit the Union National Bank and apply for a short-term loan. Ernie tells of asking banker Henry Detwiler to borrow the money for 60 days, and then paying it back in 30.

They would travel to Main Street in Telford for groceries at the original Landis store. Founder Frank Landis would call out the prices of each item, one by one, and his wife Sadie would ring them on the cash register. Miller’s variety store in Souderton offered a little of everything, while in Lansdale there was Woolworth’s. And Marie remembers buying stockings and hair nets at Sines 5 & 10 on Broad Street in Quakertown.

Ernie and Marie Hange show one of the items he kept from local businesses through the years. In this case, it’s a carpenter’s level from the local Gulf station. This item, he says, is one his children played with over the years and will be handed down in the family.

Life was a blur of family and work. Marie had worked as a babysitter before being married. And then worked in a pants factory until the children came along. After doing carpentry for a few years, Ernie moved into custom kitchens. He also had a side business using his carpentry skills. The work was all word of mouth, and the names in the red journal he kept read like a local telephone book. On each line was the customer, the job and the amount paid. He kept the journal for decades.

The family, which grew to two sons and two daughters, lived in the house Ernie built on Blooming Glen Road. He continued installing custom kitchens for 39 years, perhaps inspiring son Neal, who owns his custom kitchen company in Chalfont. Ernie officially retired at 70 but kept on working for his private customers. It was only at 81 that he gave up his business entirely.

When the children were young, there were lots of camping trips, but the couple did not wait until their “golden years” to enjoy travel. They hit the road with Perkiomen Tours, which began offering group vacation packages by bus in the 1950s. Ernie and Marie have been on many of them — 120 in total. That would include a 34-day motorcoach trip to Alaska!

Nowadays, Ernie and Marie live in an apartment attached to son Neal’s home. They have 12 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren. Of course, with age comes the loss of family and friends, along with health challenges. But Ernie proudly shows photos of the many people still in their lives from Sunday School classes. Many are younger, in their 70s and 80s. Friends, family and faith form a circle of love around the couple. They celebrate 70 years of marriage in 2022, and Ernie sums it up this way: He is 91 and Marie is 93, and he’s spent the last 70 years trying to catch up with her!

Sweet memories

Ice cream is a theme that runs through Ernie’s life. When he was young, they would hand-crank 8 quarts of ice cream made with eggs gathered from their chickens and cream from their cow.

The Pennville one-room schoolhouse he attended is now known as the Sundae School ice cream shop in Hilltown. When the owner learned that Ernie had attended school there in the 1930s, he asked to hear some stories. When you visit the shop’s Facebook page, you can watch Ernie talking about the school where parents now buy treats for their children.

The former Gehman school in Perkasie he attended went through several iterations after closing. Ernie says he saw some work being done on the building one day when driving past and stopped in to ask what was planned. He spoke with the then-owners about being a schoolboy there and that the teachers would smack your hand with a hickory stick. Ernie recounts the jingle: “Reading, writing and arithmetic — all to the tune of the hickory stick.”

The former Gehman school building. (From Facebook)

The owners loved the story and named their ice cream shop The Hickory Stick. The present owners confirm this is where the store’s name came from and that as a favor to the original owners, the name was kept when the shop changed hands.

And now the connection to ice cream in the Hange family has moved down a generation. Son Kevin and his wife Angie own the Downtown Scoop shop on Chestnut Street in Souderton.