There are a number of famous people who have come from the Souderton area: Jamie Moyer of Major League Baseball and Don Haldeman of Olympic trap shooting fame are two of them.

But if one delves back further in time, the unlikely name of Servatus S. Brey comes out of the pages of history. By reputation — and his own claim — Servatus Brey was the only man from Souderton to have served in the United States Army during the Civil War.

Servatus was born on June 20, 1840, in Marlborough Township near Sumneytown. He was the oldest child of Henry and Mary Brey, and by the time of the 1850 Census, he had been joined by siblings Addison, Sylvester, Lucinda, Henry, and Daniel.

More than likely, Servatus entered the blacksmith trade as an apprentice to an experienced blacksmith in the area, as was the practice at the time. He would have started out sweeping floors, cleaning up the work area, delivering items, and a variety of other menial tasks. Eventually, he would have acquired the skills required for blacksmithing and entered into the trade as a skilled craftsman in his own right.

Servatus settled into life as a blacksmith and established himself with wife Lucinda Shueck and two children. Son Henry was born on May 31, 1860, and daughter Mary Ellen followed on April 30, 1862.

But the most monumental event in American history to that date interrupted what would have been a normal family life. The Civil War, which started in April 1861, disrupted the lives of millions of young men and women, North and South. Servatus Brey was one.

Likely over the objections of his young wife, Servatus decided to answer the call to arms that had gone out throughout the northern states. His decision wasn’t forced by the draft, which didn’t begin until the summer of 1863. And it wasn’t a financial decision, as a private in the United States Army earned only $13 a month — much less than the average $3 per day a blacksmith could earn. So, it could be that he made his choice willingly, perhaps driven by the patriotism that swept both the northern and southern states at the start of the war a year earlier.

On Aug. 20, 1862, Servatus traveled to Norristown and enlisted as a private in Company K of the 138th Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment. Eventually, 944 men would serve in the regiment by the time it mustered out at the end of the war in 1865.

It’s likely that the army made use of Servatus’ skills as a blacksmith — a valued trade. A blacksmith would make or repair the metal parts of the soldiers’ weapons and fix the wagons and wheels on the tens of thousands of vehicles needed to move the army. And, of course, make horseshoes for horses, hundreds of thousands of which were used in the war.

The company muster roll — a record of each soldier’s service time — obtained from the National Archives does note that Servatus served extra duty off and on from 1863 as a “wagoner” or teamster. He would have been responsible for driving and maintaining his wagon as well as feeding and caring for the mule team that pulled it. And his cargo, which was his responsibility to deliver safely, would have been just about anything: food, medicines, weapons, ammunition, clothing, tents, tools, etc. It was an essential job.

But not carrying a weapon in no way ensured that Servatus would have stayed behind the frontlines in the battles in which the 138th regiment fought. Whether blacksmith or wagoner, he would have been needed to be nearby during a battle. Servatus would have been right in the thick of the fighting with his comrades, sometimes picking up and using a weapon himself if the situation became desperate.

And the 138th often faced desperate situations. While it spent the first 14-15 months engaged in mundane tasks such as garrison duty, escorting supply trains and patrolling in rear guard areas, this quickly changed in November 1863. From then until the end of the war in April 1865, the regiment served in at least 14 battles and campaigns, including:

• Mine Run Campaign (November–December 1863)

• Battle of the Wilderness (May 1864)

• Battle of Spotsylvania (May 1864)

• Battle of Cold Harbor (June 1864)

• Battle of Monocacy (July 1864)

• Shenandoah Valley Campaign (August–December 1864)

• Battle of Cedar Creek (October 1864)

• Siege of Petersburg (December 1864–April 1865)

• Sayler’s Creek (April 1865)

• Appomattox Campaign (April 1865)

When Servatus mustered out on June 23, 1865, there were 543 men remaining from the original 944 within the regiment; 167 men died in combat or from their wounds and disease. The others had been discharged for unrecoverable wounds, illness, and a variety of administrative reasons. Bluntly, one out of every six men that Servatus served with during his three-year enlistment never made it home. It was a grim record that must have weighed heavily on him for the rest of his life.

Servatus returned home and resumed his profession as a blacksmith, working in the Woxall, Sumneytown and Naceville areas. In 1883, he relocated his family and business to Souderton, where he would continue to work for the remainder of his life.

Initially, his blacksmith shop was located in the rear of Tyson’s Hotel at the corner of Main and Green Streets. In April 1890, the Souderton Independent reported that he moved his shop to the rear of what was then known as the W.D. Hunsberger hardware store on East Broad Street. The blacksmith’s shop was built especially for him, the newspaper reported.

The Hunsberger store and home in 1886, despite what was written on the photo. The blacksmith shed was at the rear of the store.

Throughout the years, Servatus stayed connected to his former regiment. Newspaper articles reported on his trips. For example, on June 22, 1894, Servatus “accompanied the excursion from Schwenksville to Gettysburg. He returned home on Monday a tired man but well pleased with the trip to the battlefield.”

On September 23, 1898, the paper reported that, “S.S. Brey, the well-known blacksmith, and a veteran of the civil war, on Monday left for Frederick, Md., to visit the battlefield of Monocacy, where his regiment, the 138th Pennsylvania Volunteers held their annual reunion on Tuesday of

this week.” The article continues, “Mr. Brey enjoyed the trip very much and speaks well of the good time he had with his comrades.”

On Sept. 8, 1899, the Independent reported that “a large number of our citizens attended the G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic) Encampment at Philadelphia during the week. S.S. Brey, the only veteran in town, took part in the parade on Tuesday.”

But several weeks later, in late October, the newspaper reported that Servatus was “seized with an attack of paralysis while engaged in shoeing a horse. The attack was not severe at first, but Mr. Brey felt that something was wrong with his left side. He started for Freed’s hotel (today’s Old Indian Valley Inn) and when at the door dropped to the floor. He was assisted to a chair and Dr. E.N. Souder summoned.”

On Oct. 27, 1899, his obituary reported the end of the story:

Sarvatus S. Brey, an old and esteemed citizen of Souderton, died at 5:40 o’clock on Tuesday afternoon. On the 9th inst. He was seized with a severe attack of paralysis, while at work in his blacksmith shop. He was conveyed to his home, where his condition became worse, until the end.

For four days previous to his death, he was lying in a comatose condition.

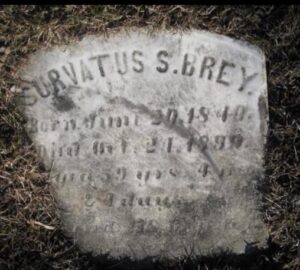

Brey’s gravestone in the cemetery of what is now Jerusalem Evangelical Lutheran Church.

He was 59 and survived by his wife and children. The newspaper also reported that his mother Mary Brey “is still living and was at his bedside during the sickness.”

His grave marker in the Jerusalem Union Cemetery in Almont, West Rockhill Township, shows he died on Oct. 24, the Tuesday referenced in the article. It goes on to say that the funeral for Servatus was held Saturday, Oct. 28, and the burial was held that day at the Schlichtersville Church, as it was known at the time.

On Nov. 11 — the date now commemorated as Veterans Day — an auction of his personal property was held.

The final mention of Servatus Brey was the note in the newspaper that his widow Lucinda, now living in Tylersport (likely with her daughter’s family), would receive a war pension of $8 per month — worth roughly $300 today. The pension was granted “by the persistent work of our Notary Public B.D. Alderfer and Congressman Irving P. Wanger.”

Lucinda Brey later died in the home of her son at Brick Tavern.

Servatus Brey was a man who had the rare opportunity to have lived both an ordinary and extraordinary life. His efforts throughout his life contributed to the health of a family, the growth of a community, and the survival of a nation. Like others before and after him, we are proud to have Servatus Brey as a part of Souderton history.

End note: Was Servatus Brey the only U.S. Army Civil War veteran from Souderton, which is how he described himself?

While the prevalence of the pacifist Mennonites in this area make that claim a possibility, it’s still unlikely that a town the size of Souderton would have had only one Civil War veteran. A special schedule of the 1890 Census — completed in June — identified living veterans of the “war of the rebellion” or their widows living in Souderton. Enumerator Samuel Benner found five men who were veterans; three of them served in units from other states.

But Simon Renner and Servatus both served in the 138th Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment. Simon enlisted in Company J on the same day that Servatus enlisted in Company K. Simon served six months before being discharged on a “surgeon’s certificate,” while Servatus served to the end of the war.

So more than one Civil War veteran did live in Souderton as the century ended. We can’t say whether they knew about each other. But what is clear from the newspaper reports is that Servatus’ status as a veteran of that traumatic time was respected by the community.

And about that name … Our veteran’s name can be found spelled as Servatus, Sarvatus, and Survatus. It appears in one or the other form on his obituary, his military record, and his gravestone! However it was spelled, Servatus is the Dutch form of “Servatius.” A Roman Catholic saint, Servatius helped spread Christianity to the Low Countries of Europe in the 4th century. The name derives from the Latin word meaning to “save or to preserve.”