The winter of 1882 was waning. Bright, warm spring was just a few weeks away. But the “good people” of Telford were worried. Strange things had been happening in town for weeks, and anxiety was spreading. The Souderton Independent carried a column from the Telford correspondent in March:

Horses die, children get sick, cows cease to give milk, chickens crow and don’t lay eggs, cats wander about homeless, dogs bark at the moon, and who knows what else … has already been brought about, of which the sufferers never tell, for fear they will be worse dealt with in the future.

People were scared and apparently willing to believe the unimaginable. Powerful, supernatural forces were at work. Someone in Telford had sought the advice of a fortune teller from Philadelphia, who pointed a finger at the source of the “mysterious and malicious” acts:

Telford was home to a witch.

The columnist didn’t know the target of this accusation, although many did. He assumed it was a woman, “because we have never known of a man being suspected of witchery.” And he was worried. “Where to find a remedy for this affliction is a question which is agitating the minds of many people … because we fear the worst, if nothing is done in this matter immediately.”

Based on the history of witch hunts in Europe and the early American colonies, the columnist was right to be worried.

Medieval Europeans were vicious in their pursuit of alleged witches. In German lands, thousands of women were tortured and killed after a monk named Heinrich Kramer published a book in 1486 in which he argued that witches did exist, explained the best ways to detect witchcraft, and then presented a legal and Biblical grounding for their persecution. The book was so misogynistic and his actions so distasteful — his questioning of accused women was often of a sexual nature — that even many of those who ran the Inquisition condemned it. Regardless, it was the handbook for witch hunts for centuries.

Witches being burned at the stake in Derenberg in a 1555 leaflet.

As early as 1542, witchcraft was made a secular crime under English law, and for the next 200 years, witch hunts regularly swept through English and Scottish towns. This hysteria was brought to the colonies, where the Salem witch trials of Massachusetts took place in 1692. More than 200 people were accused, 30 were found guilty, 20 were executed and others died in jail.

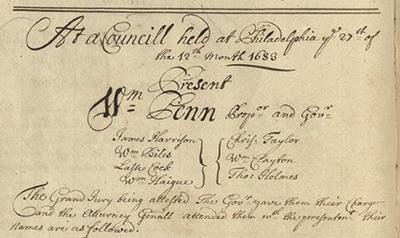

Pennsylvania’s one and only witch trial took place in 1683, a decade before Salem. But in this Quaker colony, the outcome was decidedly different. The case of the “witch of Ridley Creek” started when cows began acting funny. Two women, Swedish immigrants, were charged with cursing cows and casting spells. William Penn himself presided over their trial and ensured that it was a fair one. An interpreter was provided, several Swedes sat on the jury, and defendant Margaret Mattson spoke on her own behalf — none of which was typical in the 17th century.

The trial record for Margaret Mattson

Nor did the risk of capital punishment hang over the women since Penn had abolished it for all crimes except willful murder. Although it may be a legend, Penn was said to have asked:

“Art thou a witch?” Margaret denied that she was. “Hast thou ever ridden through the air on a broomstick?” In some reports, a confused Margaret answered yes. “Well, I know of no law against it,” Penn said.

Margaret and her co-defendant were found guilty of having the reputation of being witches — which wasn’t a crime — but not guilty of the crimes of which they were accused. Their husbands paid a bond of 50 pounds each, which would be returned if no further charges of witchcraft were filed for six months. Margaret presumably behaved herself and that was that. (Note: This article from The Pennsylvania Lawyer is worth the read for more on the trial.)

Pennsylvania in 1718 did make witchcraft a capital crime when the colony adopted English law. But this was repealed in the 1750s, and it appears no other Pennsylvanian since 1683 has faced trial on charges of witchcraft. Which is interesting given that Pennsylvania Germans practiced ritual healing known as powwow, or Braucherei. The proper placement of a broom by the front door, for example, was believed to protect from malicious people and spirits. One could remove warts with a potato by the light of the waxing moon. Eggs laid on Good Friday were concealed in the attic for protection of the house and farm. Although such folk practices were seen in other immigrant communities in later decades, in colonial America they surely would have been viewed with suspicion by outsiders.

Fast forward 199 years to Telford in 1882.

No mention of the Telford witch appears in the newspaper again until May, when a lengthy “Dear Editor” column was printed. Its author, unidentified by name, began by writing:

In the opinion of all right-minded and intelligent people of the village of Telford and vicinity, that time has arrived to put an end to the malicious and uncalled-for attack on one of our esteemed citizens and his family.

Dear Editor wrote that he had been authorized by the “shamefully abused family” to share publicly that only three weeks earlier, they had been told by a friend “how people for the last six months at least, without any knowledge of theirs, pointed out the mother of said family as a Witch, ascribing the powers of darkness to her and hers.”

The husband told Dear Editor that he feels “greatly humiliated and ashamed at being thus dealt with in his own neighborhood. … In what manner, shape or form … have we wronged any of our neighbors? We would rather wrong ourselves than wrong innocent babes and dumb beasts.”

The author injects parenthetically — and perhaps sarcastically — that now would be a good time for black cats straddling broomsticks to appear on stage. “It is a lamentable fact that at the close of the nineteenth century A.D. that should in an enlightened community still remain the seeds of barbarism, idolatry and gross superstition.”

Dear Editor recalls the Biblical story of King Saul and the witch of Endor, presumably familiar to people of faith in the community. Saul had asked God for help in defeating the Philistine army in battle but had received no answer. Although he had outlawed the practice of sorcery in Israel, Saul disguises himself and asks the witch to raise the spirit of the prophet Samuel to prophesize about the coming battle. The spirit is upset at being disturbed, he scolds Saul for turning from God, and predicts that Saul and Israel will be defeated. Which they were.

Dear Editor draws a parallel between Saul, who turned to dark forces when he felt God was not listening, and those in Telford who would accuse a neighbor of practices that people of faith should reject. Are we “ashamed of our father in heaven and have to seek after strange gods?”

The author reminds readers that 200 years earlier, the people of Salem did the same. The persecutions of their neighbors happened because of “religious fanaticism, coupled with ignorance of organic and physical laws.” What excuse do the people of 1882 Telford have, with its many houses of worship and schools? “It is nothing but gross ignorance, the superstructure of which is Aberglaube (superstition).”

“Brethren, these things ought not so to be.”

It seems Dear Editor shamed the community and broke the chain of rumor that had enveloped Telford for months. No further mention of the Telford witch appeared in the newspaper. And as far as we can find, the family’s name did not make it into the public record despite so many knowing who they were.

That restraint would be welcome in today’s social media-driven world, in which anything can be said about anyone with little accountability. But there are other lessons to learn from the story of the Telford witch. Certainly, how easily and quickly a community can be divided against itself. That people of faith can be led astray when they fail to practice what they profess to believe. And that one voice speaking truth to evil could change what might have become a tragedy.