When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, the residents of Souderton and Telford responded with great enthusiasm by supporting those serving overseas, in U.S. camp hospitals or on military bases. The war had broken out in Europe in 1914, devastating allies France, Belgium, Britain and Russia. When the United States began sending fresh troops to France in late 1917, it felt as if the Americans were coming to save the day. Little did we know one of the roles the United States would actually play in the Great War.

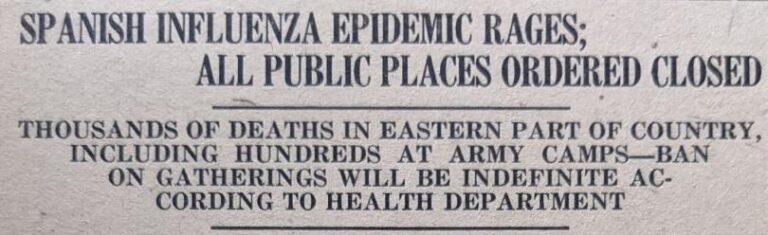

Souderton Independent on Oct. 11, 1918

At home in Souderton, the Soldier’s Welfare Society was formed, led by sisters Stella and Eva Souder of West Broad Street and Mrs. Henry (Katie Loux) Weidemoyer of Hillside Avenue as chairlady. Bazaars and benefits were held on behalf of those serving. The committee members tirelessly raised money and collected items such as towels, soap and newspapers to be sent to the men.

On Sept. 26, 1918 — two days before Philadelphia held what would be its fateful Liberty Loan parade promoting government bonds to pay for the needs of the allied troops — Souderton held its second Liberty Sing on the Chestnut Street school grounds, promoting the fourth Liberty Loan. People began congregating there in large numbers, while at the Electric Mirror Theatre on East Broad Street, a war film was being shown. In Telford, folks began canvassing door to door in order to meet its bond quota.

Perhaps it was a blessing that it rained during the Liberty Sing, keeping participation somewhat lower than anticipated. Or perhaps it really wouldn’t matter, after all.

All small-town newspapers of that time period shared personal items, much like our social media today. Subscribers knew who went visiting or was visited, who was moving in or out and where, and who was injured or sick. In the same issue where the Souderton Independent newspaper was urging residents to attend the Liberty Sing, it was casually noted that in Souderton, all seven members of the Warren H. Price family, Mrs. Abram B. Price, Ralph and Mildred Landes, Mrs. Norman Frederick and son Alfred, were all sick with the grippe, a common name for influenza. What later became known as “Spanish influenza” had struck home.

Spanish Influenza, Spanish Lady, or Purple Death was actually an avian flu that originated in the United States. It was first recorded in one of the military camps in Kansas. Reading about the symptoms of this influenza virus is not for the faint of heart. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) paints this vivid picture: “No matter what they called it, the virus attacked everyone similarly. It started like any other influenza case, with a sore throat, chills and fever. Then came the deadly twist: The virus ravaged its victim’s lungs. Sometimes within hours, patients succumbed to complete respiratory failure. Autopsies showed hard, red lungs drenched in fluid. A microscopic look at diseased lung tissue revealed that the alveoli, the lungs’ normally air-filled cells, were so full of fluid that victims literally drowned. The slow suffocation began when patients presented with a unique symptom: mahogany spots over their cheekbones. Within hours, these patients turned a bluish-black hue indicative of cyanosis, or lack of oxygen.”

By Oct 4, 1918, 200 cases of influenza or the accompanying pneumonia were noted in Souderton, a town of 3,028 residents. More than 100 children were absent from the schools, and Howard Vincent P. Frederick of West Chestnut Street had died at age 34, leaving his wife and four young sons. Sixty-two deaths were reported at Camp Dix, N.J., and a total of 20,000 new cases were reported in U.S. military training camps. It was estimated that 10% of the population of Philadelphia was sick. There were not enough doctors, nurses, morticians or grave diggers to handle the crisis. So many had volunteered for the war effort.

“Philadelphia lost nearly 13,000 people in a matter of weeks. Overwhelmed with bodies, many cities soon ran out of coffins, and some had to convert streetcars into hearses to keep up with demand.” — Pan American Health Organization

In some cases, there was no choice but to dig a loved one’s grave. Telford undertaker Howard C. Hetrick volunteered his services in both Lansdale and Philadelphia, and workers at Hemsing & Son’s planing mill, located on East Chestnut Street in Souderton, assisted Souderton undertaker Enos S. Moyer in making coffins.

The United States, its allies, and the Central Powers — the coalition of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria — all censored newspaper reports about the effects and extent of the influenza.

They “stifled reports to hide information that could be used by the enemy. However, uncensored newspapers in Spain openly reported the deaths from flu of millions of Spaniards in May and June of 1918 — reports that were picked up by media around the world. Spain, outraged at the unflattering epithet, pointed its finger at France, saying the disease had come from its battlefields and had flown over the Pyrenees mountains carried by the wind. The misnomer, however, endured.” — Pan American Health Organization

To this day we still refer to it as Spanish Influenza, although the sobering fact is that it was American soldiers who spread the disease to France.

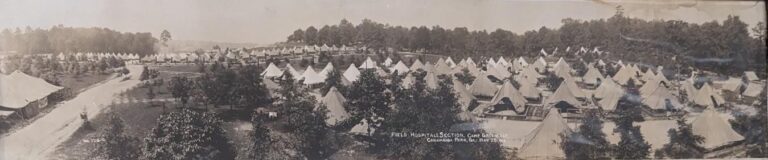

Souderton soldiers Raymond Ritter, stationed at a training camp in France, and Garland Bissey at Camp Greenleaf in Georgia, contracted influenza. And both recovered. But once the influenza reached the battlefields, the epidemic quickly exploded into a pandemic.

Photo of the Field Hospitals Section, Camp Greenleaf, Chickamauga Park, Ga. May 29, 1918

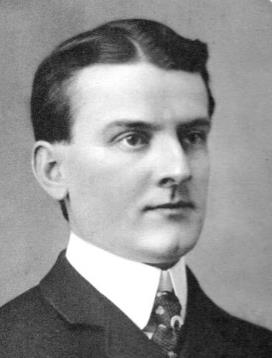

Private Norman K. Egolf of East Summit Street, serving with the 315 Inf. 79 Div. Pennsylvania, was sent to a military hospital “somewhere” in France for treatment of his feet after a long hike. While there as a patient, he contracted Spanish Influenza. The disease worked rapidly, and pneumonia killed Egolf on Oct. 8, 1918. He was buried in Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, Romagne, France. (video) Some small solace for Egolf’s widowed mother was knowing that his nurse attended his funeral and burial. She wrote to his mother informing her that she had remained with him to the very end.

Pvt. Norman K. Egolf

Extremely baffling was that this influenza brought down young, seemingly healthy individuals. It struck pregnant women. Soudertonian Horace K. Underkoffler — who proudly had opened his plumbing and electrical store on South Front Street at the age of 31 — died three years later, on Oct. 8, 1918, one week after his 34th birthday. He left behind his wife Laura and three young children.

Sounding all too familiar from our own recent experiences, by Oct. 11, 1918, Pennsylvania health officials had ordered mandatory closing of theaters, public halls, schools and churches. Some local businesses were ordered closed. Large gatherings such as the Liberty Loan rallies were prohibited. Only private funerals were to be held.

Still considered an epidemic at home, people were urged to sleep with their windows open and not to share drinking cups. The Young Women’s Christian Association (Y.W.C.A.) began sewing face masks. It was believed that this epidemic would last, at the most, six weeks. By now, 500 influenza cases were reported in Souderton, 40 in Telford, and 350,000 in the state. In Souderton, there were six deaths.

By Oct.18, 1918, Dr. J.K. Frederick of Telford was sick with pneumonia. He survived. It was reported there were three Telford residents and six from Souderton with extreme cases, along with three more deaths.

A week later, Oct. 25, more people in Souderton and Telford were improving than were contracting the disease, although three more deaths in both towns were recorded. Many people appeared to be improving, only to suffer a relapse.

Romandes Goettler

Romandes B. Goettler, junior editor of the Souderton Independent, was one. He came down with a serious case of the flu in January 1919, suffered at least one relapse, and was terribly ill for more than two months. When he died in 1930, his obituary stated he had never fully recovered from the Spanish Influenza and had been in a weakened condition for the rest of his life.

Amid reports cautioning people not to relax diligence on spreading the disease, and headlines reporting that influenza was still raging, Montgomery County began lifting restrictions in 1918. Schools reopened Oct. 30, churches Nov. 3, and all other entertainments were opened on Nov. 5.

Jacob S. Moyer, who provided the Thanksgiving turkeys, announced that his supplier, Frank T. Smith of Shippensburg, had died of influenza. There would be no Thanksgiving turkeys, but he would have a new supplier in time for Christmas 1918.

Soldiers Welfare Society workers Eva Souder — who had married during the pandemic and was now Mrs. Henry C. Bergey — and her sister Stella Souder both contracted severe influenza cases, along with their younger sister Marion, who also had joined the Society. All three survived. (A later photo, below, shows the three Souder women with their husbands.)

But “just as the birds caroled the coming of the morning and just as the rosy fingers of the orb of day tinted the eastern sky with a sheen of glory” — as her Nov. 22 obituary in the Souderton Independent noted — Katie Loux Weidemoyer, chairlady of the local Liberty Sing committee, passed away the morning of Nov. 21, 1918, age 24. Her death came six weeks after the influenza death of her sister Lillian Leopold, 26, of Philadelphia, whose husband was away at war.

By November 1918 the disease was waning, but the aftermath was being felt. In coal-mining areas, between men serving in the war and those dead of influenza, a coal shortage developed in 1919, adding to the nation’s troubles.

Stella Souder Yocum, Marion Souder Godshalk, seated in front, and Eva Souder Bergey. The men, from left, are John G. Yocum, E. Stanley Godshalk, and Henry C. Bergey.

The Spanish Influenza was declared over in April 1920. The final death in our area came when John C. Fry died on May 3, 1920, two days after celebrating his 23rd birthday. He lived in the Reliance section of Souderton near Telford and had been sick for two weeks, in a weakened state since serving in WWI.

Today, the Centers for Disease Control Division of Global Migration and Quarantine uses the Philadelphia Liberty Loans Parade as an example of how not to handle a pandemic. Nine days prior to the parade, the Spanish Influenza struck Philadelphia when a Navy ship from Boston docked, flooding the naval base

with 600 ill sailors. Not only was the parade not canceled, but more than 200,000 people attended, 20 times more than projected.

“The United States lost 675,000 people to the Spanish Flu in 1918 — more casualties than World War I, World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War combined,” reported the Pan American Health Organization. The National Archives estimated that 50 million people succumbed worldwide, and 500 million people were infected.

Author’s note: While I don’t have all the names of the people who contracted the Spanish Influenza in Souderton and Telford, I do have some. I have the information for those who died. By my count, 25 people from Souderton died and seven from Telford. If you believe one of your relatives may have been sick or died during this time, please feel free to contact the Souderton-Telford Historical Society, and I will be happy to share my information. Email to: newsletter@soudertontelfordhistory.org

For further reading: Check out the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC) and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).