Young Warren Royer was “looking fine” in March 1918 when he visited his parents at 45 Penn Avenue in Souderton. He was on furlough from Army Camp Hancock in Georgia when his visit was noted in the Souderton Independent. In early May, Warren was on his way to France, where he arrived safely in late May 1918.

Warren Royer enlisted on July 6, 1917 and was killed on Sept. 29, 1918, at the age of 21.

Five months later — and only a few weeks before an armistice ended the Great War at the 11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918 — his parents, William and Hannah (Neff) Royer, received the official message from Washington, D.C., that Sergeant Warren Royer, Infantry, had been killed in action in France on Sept. 29. “Particulars are awaited,” the newspaper said.

Warren was one of several dozen young men from Souderton and Telford who served during World War I. But it is Warren Royer’s memory that has been honored 100 years beyond his death as the namesake of the American Legion Post in Souderton.

As the nation commemorates Veterans Day 2024, the historical society undertakes to preserve and share the story of Warren Royer and his namesake American Legion post 234, which was chartered less than a year after he died. In this Gazette, we focus on Warren’s story.

Richard L. Freed was Warren Royer’s nephew. Richard — “Dick” to all who knew him — passed away in August 2023, and his son Rick shared with the American Legion post the history his father had written about Warren. That history is excerpted here, along with original research by the historical society.

According to the 1930 U.S. Census, Richard, his brother Robert, and his parents Delilah (Royer) and Henry Freed were living with Warren’s parents in Souderton. Warren’s sister Katie was also living there, so memories of his uncle would have been front and center through Richard’s childhood as younger siblings Gloria, Margie and William came along.

Warren was born at Bergey, Upper Salford Township — the family later moved to Souderton — on April 3, 1897, the fifth child of William and Hannah Royer. He had two older brothers, Harry and Arthur, and two older sisters, Katie and Emma. After Warren, sisters Helen and Delilah completed the family. Emma and Helen died in infancy, and only Harry and Delilah went on to have children.

Not much about Warren as a boy was passed to the next generation. He did play baseball and was once hit in the chest by a baseball bat, causing severe bruising. His nephews found his beautiful black and yellow bat, which they repaired with screws and tin tape. It was played with until it broke again beyond repair.

Warren grew into a handsome man, 6 feet tall, 170 pounds and well-liked by all he met. He likely had an 8th grade education and worked in the Souderton pool hall and bowling alley on Main Street. He became an excellent billiard player and shot pool for the house. He was financed by the owner of bets placed by other players, as well as himself, on the outcome of various games. If he won, he received a portion of the owner’s earnings.

He smoked cigars and had a girlfriend. Warren enlisted in the Army when his boss refused his request for a raise. His parents were not in favor of his enlistment, but he most likely would have been drafted into the service eventually. It was wartime; the United States had entered what was then called the Great War in April 1917.

Warren did tell his mother that if he didn’t return home from France, sister “Lilah” should get his small savings account. He was home on furlough once before being shipped overseas. A final opportunity to visit home before sailing from New York was missed because he didn’t have sufficient funds to make the trip, and the money sister Katie sent him wasn’t received.

He left the United States for France on May 2, 1918. Six weeks later, on June 30, 1918, his unit — Company A of the 109th Infantry, 28th Division — arrived on the front lines. The division saw action in all of the American Expeditionary Force’s battle campaigns of World War I, from the Marne River in June through the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, Sept. 26 to Nov. 11, 1918.

His letters home were cherished, saved, and stored in the attic, as were his service medals and Purple Heart. Nephew Richard read his letters as a boy, fascinated by his having been in a “skirrnish the other day.” The letters and medals disappeared, probably when the attic was converted into a bedroom and later a game room. (Richard was able to replace the medals with the aid of Rep. Jon Fox in 1996 and added Warren’s dog tag to the collection.)

His nephew assumed Warren must have been a fine soldier because he was promoted from private first class to corporal in less than six months, and then to sergeant three months later. An infantry sergeant leads a squad of 10 to 15 soldiers. To attain the rank of sergeant so quickly was unheard-of in the peacetime Army.

The battle in which Warren died, according to the 28th Division’s history from which Richard Freed quoted, “was the greatest struggle the division had in its fighting career. … Officers who were at Apremont solemnly vouch for the fact that there was a time in that town when the water running in the gutters was bright red with blood, and not all of it was German blood.”

Warren’s death was reported by First Sergeant Edward Smith of Philadelphia. “Royer was killed in the Argonne drive Sept 29, 1918, just south of Apremont. … I couldn’t see where he was hit. He was laying on his side and was breathing his last when I [found him]. His lips were moving, but I couldn’t hear what he said.”

Two strange events occurred that day in Souderton, as reported later in life by Warren’s mother and sister to his nephew. A white dove or bird appeared on a fence in the backyard, which was unusual, and was thought to indicate an ominous event. On the same day, Warren’s brother Harry reported that blood appeared on his automobile’s windshield as he drove from work to Souderton. He stopped and confirmed that there was blood on the windshield but couldn’t determine that he had hit anything. Again, there was alarm at what was seen as an omen.

Exactly one month later, on Oct. 29, the family received the telegram informing them of Warren’s death.

In later years, Arthur, Warren’s brother, recounted that World War I ended at the time he joined his unit overseas. Arthur used to look for Warren because he didn’t know for months that his brother had been killed in action in September 1918.

Pvt. Elmer Freed

Elmer Freed from Souderton, who was no relation, also enlisted and served in the same unit as Warren. Elmer was wounded the same day that Warren was killed and was reported as missing in action for several weeks. The Royer family always thought Elmer was with Warren the day he was hit, but this was never confirmed.

Elmer wrote often to his family, but on Jan. 3, 1919, a letter from him dated Dec. 9, 1918, was published in the Souderton Independent.

“Just a few lines to let you know I am still alive. During the first battle I never expected to see Souderton again.”

He mentioned Warren Royer. “I am very sorry to report the death of my best friend in the Army, Warren Royer. We were together since we left Camp Hancock. He was the only fellow from town with me in the first battle as Marvin Nice got shellshocked. … Now I am the only Souderton boy in the 28th Division since ‘Bill’ died bravely for his country. … War is hell. It is all right to read about it, but different to be in it.”

As was customary, Warren’s body was wrapped in a blanket and buried Sept. 30, 1918, near where he fell at Apremont. His body was disinterred and reburied on April 28, 1919, in the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery.

At the request of the family, his body was exhumed and shipped home. It arrived on the ship Wheaton in Hoboken, New Jersey, on Aug. 20, 1921. His casket was accompanied by a soldier and arrived in Souderton on Sept. 6. Warren’s father wanted confirmation the body in the coffin was that of his son. The coffin was opened in the parlor in the presence of Warren’s father and sister Katie. They found his remains still wrapped in the blanket, wearing his uniform. There was a hole in the uniform on the left side of his chest. His dog tag, high cheekbones and several gold teeth confirmed his identity.

Warren had come home. He was buried with full military honors in the cemetery of the Hatfield Lutheran Church.

Warren Neff Royer

In the family, the memory of Warren had been passed to the next generation. As Richard Freed wrote, the children of Delilah and Harry grew up hearing tearful stories and visiting the gravesite in Hatfield each Memorial Day and July 4th. They would bring flowers and speak his name and shed tears. All of which left an unforgettable impression of devotion and love for a son and brother.

The family account preserved by Richard Freed is supported by reports in the Souderton Independent. On Nov. 22, 1918, it was reported that a memorial service for Warren Royer would be held the following Sunday at the Hatfield Lutheran Church.

On Dec. 13, 1918, the Soldier’s Welfare Society in Souderton held a “minute of respect” for Warren Royer, Norman Egolf 2 and William Saxe Jr. “It may be some comfort to you to think that your loved one bore his cross in a war in which high and holy principles were involved,” the society’s message to the families said.

Almost three years later, the Independent reported on Sept. 9, 1921, that Warren’s body had arrived in Souderton and that the funeral would be held in his parents’ home at 45 Penn Avenue the following Sunday.

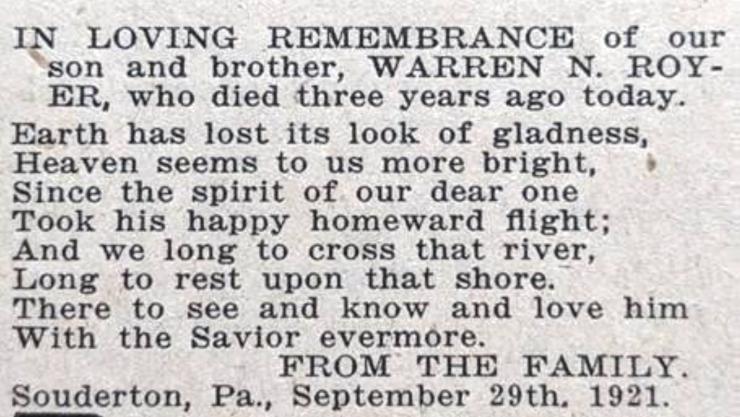

Royer family memorial notice published in the Independent.

The funeral was “very largely attended. … A very large number of people gathered at the Grace Lutheran Church and the cemetery, at Hatfield, to view the laying to rest of the body of the World War hero.”

The newspaper also reported that due to the rain, the casket was driven to the cemetery in the hearse of funeral director E.S. Moyer rather than on a caisson.

Now you know, when you drive past the American Legion building on Main Street in Souderton, something of the man for which it is named. Post 234 has preserved Warren Royer’s memory as carefully as his family.

In fact, Warren’s service inspired three generations of soldiers in the family. Sergeant Richard L. Freed, Captain Richard K. Freed, and Captain R. Zachary Freed are all Army veterans and joined by Marine Corps Master Gunnery Sergeant Mark Freed, and Air Force physician, Lieutenant Colonel Melanie Freed.

The American Legion has done much more for veterans of the wars since that which took Warren from his family and neighbors. Look for a future historical society Gazette in which we explore that history, also.

1 See the society newsletter of November-December 2018 on the centennial of World War I.

2 We wrote about Norman Egolf in our Sept.-Oct. 2024 Gazette on the influenza pandemic.